Keeping John Kasich in the race divides the anti-Trump vote.

Two months ago, based on a computer model I developed of the Republican delegate race, I wrote in The American Prospect that the GOP’s nomination rules tilted the playing field to Donald Trump’s advantage. For Trump’s opponents, the time window for counteracting many of those advantages and winning a first-ballot nomination has passed. Now the campaign enters a new phase, as Trump’s rivals try to deny him a majority of pledged delegates going into the convention. Simulating the remaining contests based on current polling data, my model picks up an unexpected wrinkle: Trump’s strongest position comes if he loses the primary in Ohio on Tuesday.

Tomorrow marks the start of an onslaught of winner-take-all elections, which will continue for the rest of the primary season. A winner-take-all rule rewards the first-place finisher even without a majority, and therefore gives the biggest advantage when the field is divided. Two of the first winner-take-all elections take place in Florida and Ohio, the home states of Senator Marco Rubio and Ohio Governor John Kasich. Winning their home state would provide each of them not only with delegates, but also with the credibility they need for raising money and obtaining other support to continue as candidates. But if they survive, they will continue to divide the anti-Trump vote with Texas Senator Ted Cruz.

In 17 out of the remaining 29 state and territorial GOP contests, the rules will give all or nearly all of the delegates to the first-place finisher. My computer simulation for these races includes rules not only for statewide but also for congressional district-level delegates, which add complexity but make only a small difference. South Carolina has already provided an example of a state with both statewide and district-level rules. Trump still got all 50 of South Carolina’s delegates.

I estimated win probabilities for Trump using recent polling data where it was available. Where polls were not available, I assumed that individual states varied around the national median with a standard deviation of 16 percentage points, comparable to the 2012 primary season. I assumed that districts varied around the state average with a standard deviation of five percentage points, a typical amount for most states. I then converted these margins to win probabilities and delegates, and combined all 29 races using methods that I originally developed in 2004 to analyze the Electoral College.

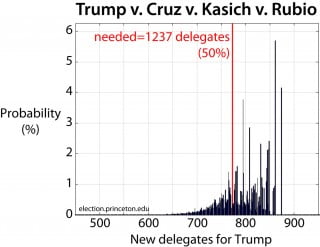

We can test the effect of a divided field by simulating the outcome of having all the primaries as if they were held today and included all four of the remaining candidates: Trump, Cruz, Rubio, and Kasich.

The above graph represents a distribution of all possible outcomes. Where polls are available, Trump leads in eight of the nine states that vote between now and mid-April. I estimate that under these conditions, he should lose between two and four of the winner-take-all races and win a median of 804 newly awarded delegates. Combined with his existing 465 delegates, Trump’s total would be 1,269, more than the 1,237 needed to get a majority on the first ballot at the convention. The total might be smaller because of chance variation, as well as Cruz’s tendency to outperform his polls. So there is a chance Trump would need to pick up a handful of additional delegates, for example from Ben Carson, who has endorsed him. In this way, Trump could easily get the nomination with a majority of delegates, despite having the support of only 39 percent of Republican voters, as measured by national surveys. Indeed, my simulation indicates even if his support dropped across the board by 5 percentage points, he would still have an even-odds chance of getting 1,237 delegates. This victory builds on the 42 percent of delegates that he has obtained so far, based on getting 34 percent of the vote.

Most of the remaining primaries, however, do not happen tomorrow. This gives time for the consequences of the March 15 primaries to unfold, changing the picture substantially.

In Florida, Rubio lags Trump by a median of 14.5 percentage points. Assuming Rubio loses and leaves the field, more of his supporters should go to Cruz than to Trump. In exit polls for Michigan and Mississippi, Rubio voters preferred Cruz over Trump by a ratio of four to one, and an ABC-Langer national sample of Republican and Republican-leaning independents got a similar split. So Trump would gain Florida’s 99 delegates, but his future gains would probably be reduced thanks to Rubio’s absence from the race.

A preview of the effects of a Rubio withdrawal can be seen in Ohio. In four Ohio polls spanning March 2 to 8, Trump leads Kasich by a median of six percentage points. Over the weekend, however, Rubio urged his supporters in Ohio to vote for Kasich, a strategic move that fulfills Mitt Romney’s recommendation to fight Trump by consolidating around the strongest candidate on a state-by-state basis. Rubio’s median support in Ohio is seven percentage points, and his supporters prefer Kasich or Cruz over Trump by a ratio of 12 to 1. So Kasich's position in Ohio may be quite competitive.

To assess the overall consequence of Rubio’s withdrawal, I redid the simulations after giving Ohio to Kasich and reassigning four-fifths of Rubio’s support in later states to Kasich and Cruz equally, with the remainder going to Trump. Under these assumptions, I calculate that Trump would gain a median of 724 delegates, to end up with 1,189 delegates in all.

Depending on exactly where Trump falls in the range of possibilities, to reach a majority he might have to gather additional support from a pool of more than 100 uncommitted and minor-candidate delegates. As more elections occur and better polling data becomes available, it will become clearer how many, if any, of these unpledged delegates he will need.

The aforementioned scenario, in which Rubio drops out and Kasich stays in, may be Trump’s best option. Perhaps counterintuitively, it is worse for Trump to win Ohio since that would likely cause Kasich to withdraw. In this scenario, Trump would be left in a one-on-one matchup with Cruz. National surveys from ABC/Langer and NBC/Wall Street Journal show Cruz leading Trump by 13 and 17 percentage points. A two-candidate race might not only leave Trump far short of a majority of delegates but also open up the possibility of Cruz ending up with the most delegates.

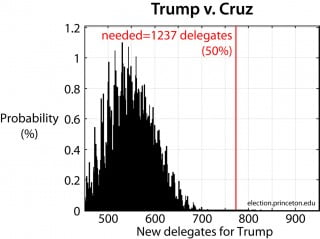

To emulate the effect seen in those two surveys, I reassigned Rubio and Kasich's support to Cruz and Trump in a four-to-one ratio. This leads to the following distribution of outcomes.

In this scenario, Trump picks up only 548 new delegates, for a total of 1,013— barely 40 percent of delegates, far short of the necessary number for nomination. Failure to get a majority on the first ballot would then generate the open convention that has been the subject of so much speculation.

Even in this two-candidate scenario, Trump still has a shot at the nomination. Despite his record of racist, sexist, and inflammatory statements, culminating in the proto-fascism and violence of his rallies, many Republicans regard him as the lesser of available evils. Some Republican insiders see the ascendancy of Cruz as more damaging to their party in the long run.

We are therefore left with an odd situation. Many Republicans who oppose Trump and Cruz are desperately hoping for Kasich to win Ohio, an outcome that Kasich himself certainly wants so that he can stay in the race. But Trump also should hope Kasich wins Ohio, since a decision by Kasich to keep fighting keeps the field divided, offering Trump himself the best chance of getting a majority of delegates and ultimately winning the nomination. The only candidate who should not want Kasich to win Ohio is Ted Cruz.

Al Zibluk